Double-entry accounting is a valuable tool for bookkeepers and accountants, providing a way to accurately manage business transactions using a system of debits and credits.

If you'd rather have accounting software handle it for you, be my guest. Otherwise, let's get into it.

What is double-entry accounting?

Double-entry accounting is the system in which business transactions are credited and debited between two accounts — an ‘action account and a ‘reaction’ account.

In any double-entry journal entry, one amount is debited and must be reflected by an equal (and opposite) credit amount in a different account.

- Debits increase the balance of asset and expense accounts, whilst decreasing the balance of liability, income, and equity accounts.

- Credits have the opposite effect on each of these accounts.

This is an effective way of maintaining checks and balances, clearly mapping how financial resources are being allocated throughout business operations.

You don't have to become a CPA to master accounting systems like this; accounting software makes the process simple.

Single-entry vs. double-entry accounting

Single-entry accounting is the most basic way to document business expenses. Under this accounting method, purchases and sources of income are consolidated into one simple list, much like a checkbook.

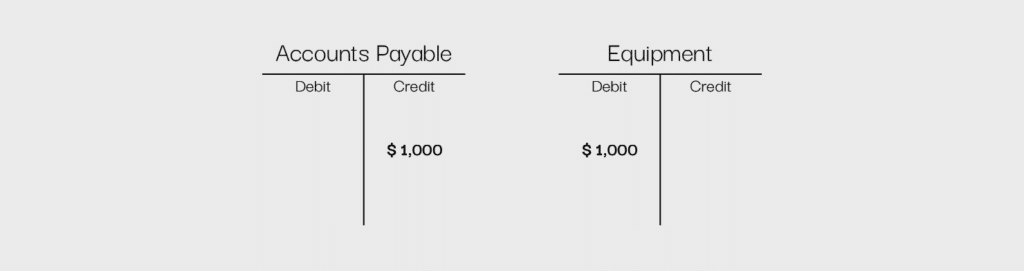

Double-entry accounting, on the other hand, acknowledges both sides of a transaction — the ins and outs, so to speak. For example, if you buy a new computer for your business, an account used to make business purchases, such as "accounts payable," would be debited, and an account related to assets, such as "equipment," would be credited. This shows that business resources were used to purchase an asset — in this case, a computer.

In a single-entry system, there would only be one line item: the cost of the computer.

Single-entry accounting may be fine for very small businesses with limited operators, as it's a simple way to document income and expenditures. However, double-entry accounting is more robust and better tracks the underlying operations of a company.

T-Accounts (T-Charts)

A T-account, also known as a T-chart, is a simple way to visualize a double-entry bookkeeping system. A large T can be drawn on a sheet of paper, with one side labeled debit and the other labeled credit.

Debit entries are recorded on the left side of the T, and credits are recorded on the right side. This way, all accounting entries can be clearly marked and separated by type.

Using the computer purchase example above, a common setup for a T-account is as follows:

Using T-accounts separates each aspect of a transaction, creating a simple and, straightforward visual representation of the expenditure.

Account Types

There are five basic kinds of accounts that a double-entry accounting system can make use of. These accounts are assets, liabilities, income, expenses, and equity. Each has a slightly different role in the course of business. Using proper accounts can help bookkeepers organize basic accounting activities for a more comprehensive overview of transactions.

Assets

Asset accounts represent the items or intangibles owned by a company, which are expected to have future benefits for said company. This includes items such as cash, equipment, and inventory, as well as goodwill and intellectual property.

To reflect increases in asset accounts, you debit them. For example, if I receive more cash as a business, I will debit the cash account.

Liabilities

Liability accounts represent forms of debt a business holds, such as explicit debt via short- and long-term loans, or implied debt such as accounts payable or unearned revenue.

To reflect increases in liability accounts, you credit them. For example, if I take on a short-term loan, I will credit the short-term loan account.

Income

Income accounts contain all sources of income a business earns, such as interest income or product sales.

To reflect increases in income accounts, you credit them. For example, if I earn additional income through a new sale, I will credit the business revenue account.

Expenses

Expense accounts include all costs associated with running a business, such as utility bills, salaries, taxes, and rent.

To reflect increases in expense accounts, you debit them. For example, if I pay my employees, I will debit the payroll account.

Equity

Equity accounts represent total shareholders’ equity in a business and include accounts such as common stock and preferred stock, as well as retained income — the difference between money invested in the business and any profit left over after expenses are accounted for.

The equity accounts “retained income” or “deficit” on an income statement are a great way to see, at a glance, how much a company has earned or lost over time. If there is a retained income account, then this business has earned more money than it has spent over time; if there’s a deficit account, the opposite is true.

To reflect increases in equity accounts, you credit them. For example, if I sell new common stock, I will credit the common stock account.

Summary

- For an asset account, you debit to increase it and credit to decrease it

- For a liability account, you credit to increase it and debit to decrease it

- For an income account, you credit to increase it and debit to decrease it

- For an expense account, you debit to increase it and credit to decrease it

- For an equity account, you credit to increase it and debit to decrease it

How double-entry accounting works

The following steps can help you successfully establish a double-entry accounting framework for your business.

Step 1: Set up a chart of accounts

First, you'll need to set up a chart of accounts. This means creating a master list of all the accounts that apply to doing business in your particular company, using all of the above types of accounts. For example, if you own business tools, such as computers or servers, you'll need an equipment account.

This process can be done manually by going step by step through all the elements that keep your business operational, or it can be easily completed through the use of software.

It may be necessary to create new accounts if the course of business changes or new income sources or expenses become relevant. This can be more complicated to handle without accounting software.

Step 2: Use debits and credits for all transactions

Once you have your chart of accounts, you can start recording debit and credit entries for your transactions.

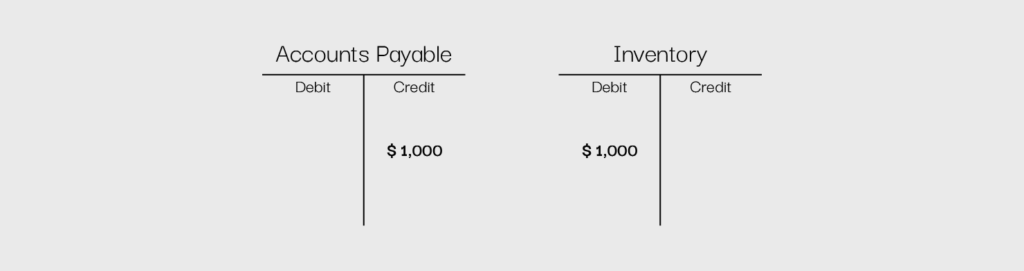

Here's an example of how you can delineate which accounts are being debited and which accounts are being credited when you buy a new computer with cash:

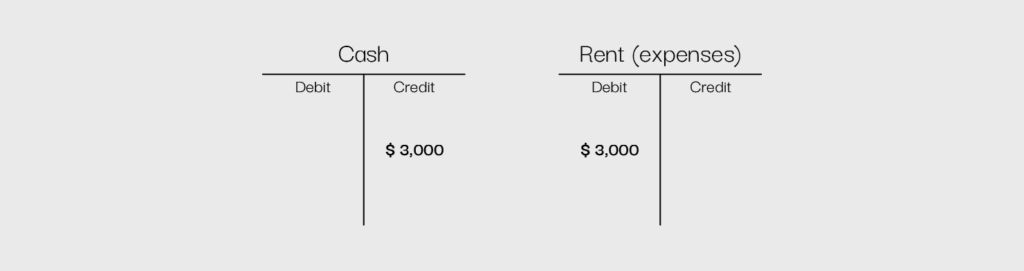

Pay rent to a landlord:

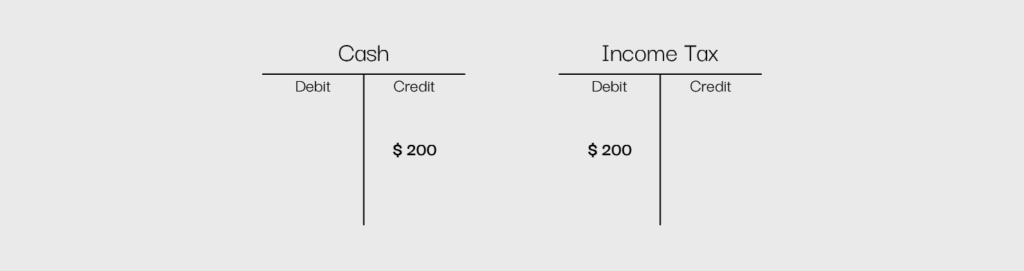

Or pay tax on income from normal business operations:

Using this simple system, you can easily see where your money is flowing and where it’s ending up.

While you can manage this process through a hand-drawn T-chart or a software program, such as Microsoft Excel, most companies use accounting software, as it allows them to keep specific, accurate records. Accounting software can minimize the likelihood of errors, as these systems are designed to ensure entries are booked properly.

For example, many programs won't allow an entry to be posted if it isn't balanced. You can also create and update financial statements simply using any type of accounting software.

Step 3: Make sure every financial transaction has two components

In double entry accounting, the most important thing to remember is that every transaction has two sides, and to maintain a balanced business, both sides must be equal. If the idea of a double entry for every transaction is a little confusing, remember Newton's third law of motion: every action has an equal and opposite reaction. If you bring your leg back to kick a ball, the energy generated by that action will cause the ball to move.

The same is true in business; every expense you pay gains you something, and every kind of income you make takes away from somewhere else, such as inventory.

Keep the basic accounting equation in mind: Assets = Liability + Equity. This means each side of your ledger must be balanced in kind; if your asset accounts aren't equal to your liability and equity accounts, there's a problem with your accounting structure.

In a non-business sense, purchasing a new computer to manage accounting and payroll for your company may seem as easy as pulling out your credit card, completing a purchase, and walking out of an electronics store. However, from a business sense, there's a little more nuance. To make your purchase, you're crediting a liability account — accounts payable, in this case. However, that money used isn't vanishing into thin air; it's being used to obtain an asset for your business, which means debiting an asset account.

Now that you've read through how double-entry accounting works and seen examples, it's time to test your knowledge!

Deciding if double-entry accounting is right for your business

Double-entry bookkeeping may sound, at times, needlessly complex, but it's a valuable tool used by companies around the world. Rather than simply listing expenses and income, businesses can break things down on a detailed level, helping decision-makers better understand how money is being used.

Ready to compound your abilities as a finance leader? Subscribe to our newsletter for expert advice, guides, and insights from finance leaders shaping the tech industry.