The free cash flow formula: your key to a happy Board and a safe job.

After all, knowing how much cash you have to play with could mean the difference between rags and riches. Overspend when you don’t have it and you’ll be dealing with angry shareholders and a disappointed bank; don’t use what you have effectively and you might as well be throwing it into the fire we call “inflation”.

But how do you calculate free cash flow (FCF)? You could choose to start from various points such as Operating Activities, Net Income, and EBIT. Each method has its advantages and use cases, and the choice of method depends on the user's needs and the information available.

I’ll walk you through what to use, when to use it, and why it matters.

What is Free Cash Flow?

FCF is a measure of a company's financial performance and health. It represents the cash that a company is able to generate after accounting for the money required to maintain or expand its asset base.

Free Cash Flow is a key indicator of a company's financial flexibility and strength. It shows how much cash a company has left over after it has paid for its operational expenses and invested in its growth. This is the cash that can be used for discretionary purposes like dividend payments, buying back shares, reducing debt, or paying your own CEO for the use of the word “We”.

Why Knowing Your FCF Matters

There are numerous reasons you need to be acutely aware of your FCF; some business critical, others as a means to lead to a better business in the long term. Here are a few of the most important reasons:

Profitability vs. Cash Generation

While net income is a measure of profitability, it includes non-cash items and can be influenced by accounting practices. FCF, on the other hand, represents the actual cash generated by the business that is available for distribution to investors after all expenses and reinvestments. It's a more tangible measure of a company's financial performance.

Financial Flexibility

FCF indicates a company's ability to generate cash beyond what is needed for operations and capital expenditures. This flexibility can be a sign of a strong, well-managed company.

Investment Quality

Positive FCF is often a sign of a high-quality investment. It suggests the company is generating more than enough cash to support its operations and growth, which could lead to increased dividends or share buybacks, both of which can enhance shareholder value.

Solvency Indicator

FCF can also be an indicator of solvency. While that may be fine for certain angel investors that want moonshot investments, most rational people prefer to know that a company can keep the lights on without having to raise more money. Companies with consistently negative FCF may struggle to meet their obligations without new cash in the system, leading to financial distress or bankruptcy.

Valuation

FCF is a key input in valuation models. For example, the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model, one of the most common valuation methods, relies on FCF to estimate a company's intrinsic value.

How to Calculate Free Cash Flow

The FCF formula can be calculated in a variety of ways; here are a few of them, differentiated by starting point.

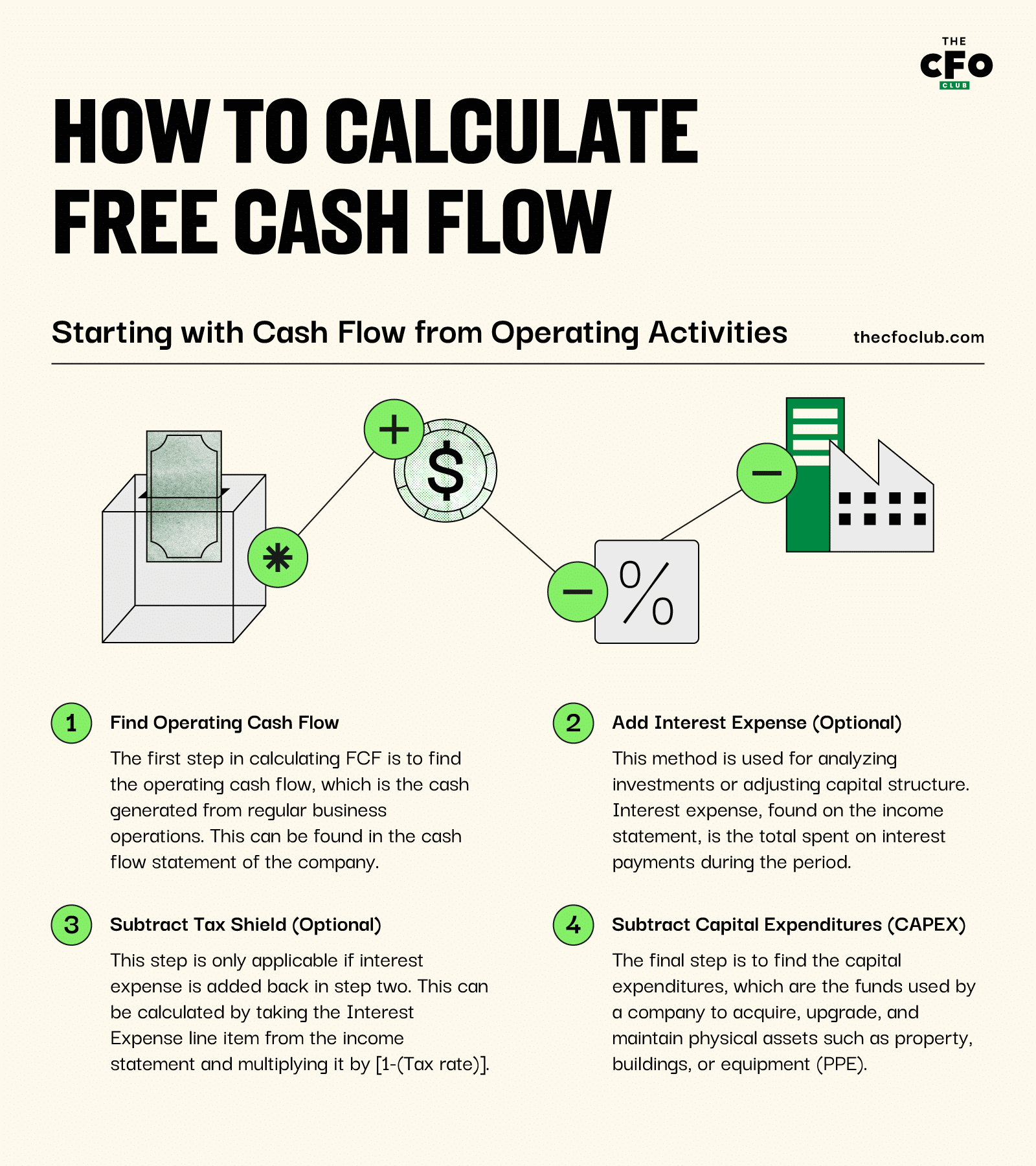

Starting with Cash Flow from Operating Activities

- Find Operating Cash Flow: The first step in calculating FCF is to find the operating cash flow, which is the cash generated from regular business operations. This can be found in the cash flow statement of the company.

- Add Interest Expense (Optional): In some circumstances, the goal of a free cash flow is to determine the amount of cash generated from the business without the impact of capital structure on the outcome (known as unlevered free cash flow). This method is mostly included when analyzing a potential investment or contemplating an adjustment to the current capital structure. The interest expense is the total amount spent on interest payments during the period in question and is usually found on the income statement.

- Subtract Tax Shield (Optional): This step is only applicable if interest expense is added back in step two. Given that interest expense is tax deductible, adding interest back means you also need to subtract the tax benefit associated with that interest expense. This can be calculated by taking the Interest Expense line item from the income statement and multiplying it by [1-(Tax rate)].

- Subtract Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): The final step is to find the capital expenditures, which are the funds used by a company to acquire, upgrade, and maintain physical assets such as property, buildings, or equipment (PPE). This is also usually found in the cash flow statement (specifically in the investing activities section).

This system is best utilized when looking at an entity's financial statements, as many of the numbers can be directly pulled from within the statements with relative ease. However, this system is not ideal without a prepared cash flow statement and, as such, is less useful when accounting for individual projects.

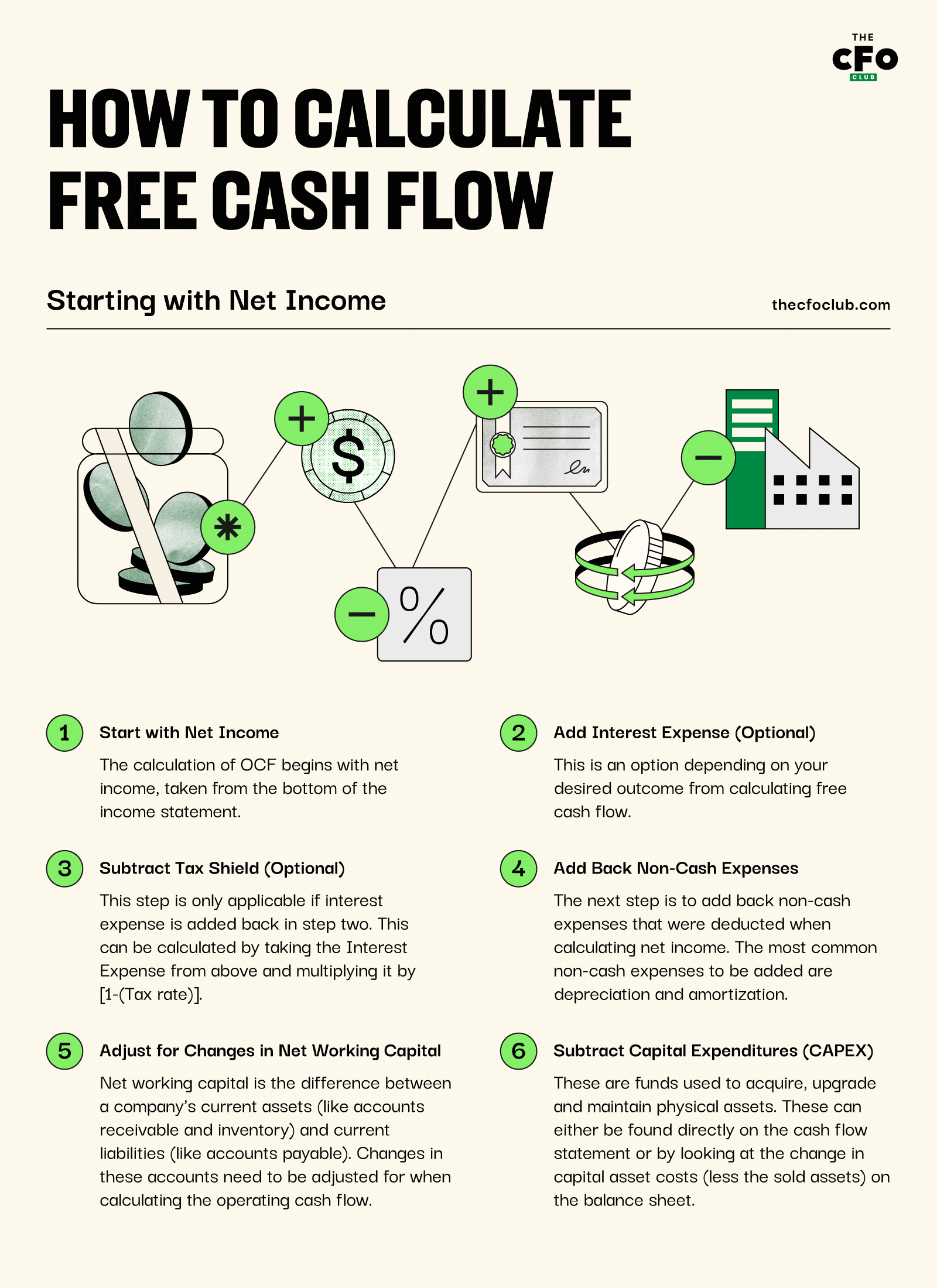

Starting with Net Income

- Start with Net Income: The calculation of OCF begins with net income, taken from the bottom of the income statement.

- Add Interest Expense (Optional): Similar to above, this is an option depending on your desired outcome from calculating free cash flow.

- Subtract Tax Shield (Optional): Again, the same as above. This step is only applicable if interest expense is added back in step two. This can be calculated by taking the Interest Expense from above and multiplying it by [1-(Tax rate)].

- Add Back Non-Cash Expenses: The next step is to add back non-cash expenses that were deducted when calculating net income. The most common non-cash expenses to be added are depreciation and amortization. Other non-cash items that might need to be added back include deferred taxes and any losses on the sale of assets.

- Adjust for Changes in Net Working Capital: Net working capital is the difference between a company's current assets (like accounts receivable and inventory) and current liabilities (like accounts payable). Changes in these accounts need to be adjusted for when calculating the operating cash flow.

- If current assets (excluding cash) increase during a period, cash flow from operations will decrease, and vice versa. This is because an increase in current assets represents a use of cash.

- If current liabilities increase during a period, cash flow from operations will increase. This is because an increase in current liabilities represents a source of cash.

- Subtract Capital Expenditures (CAPEX): Same as above, these are funds used to acquire, upgrade and maintain physical assets. These can either be found directly on the cash flow statement or by looking at the change in capital asset costs (less the sold assets) on the balance sheet.

This system may be more complex than starting from operating income; however, it has many more use cases. Given there’s no need to have a fully prepared statement of cash flows, this system can be used for anything from individual business line performance analysis to assessment of potential future projects. Plus, it can be used in all the same situations as the method starting from Operating Cash Flows.

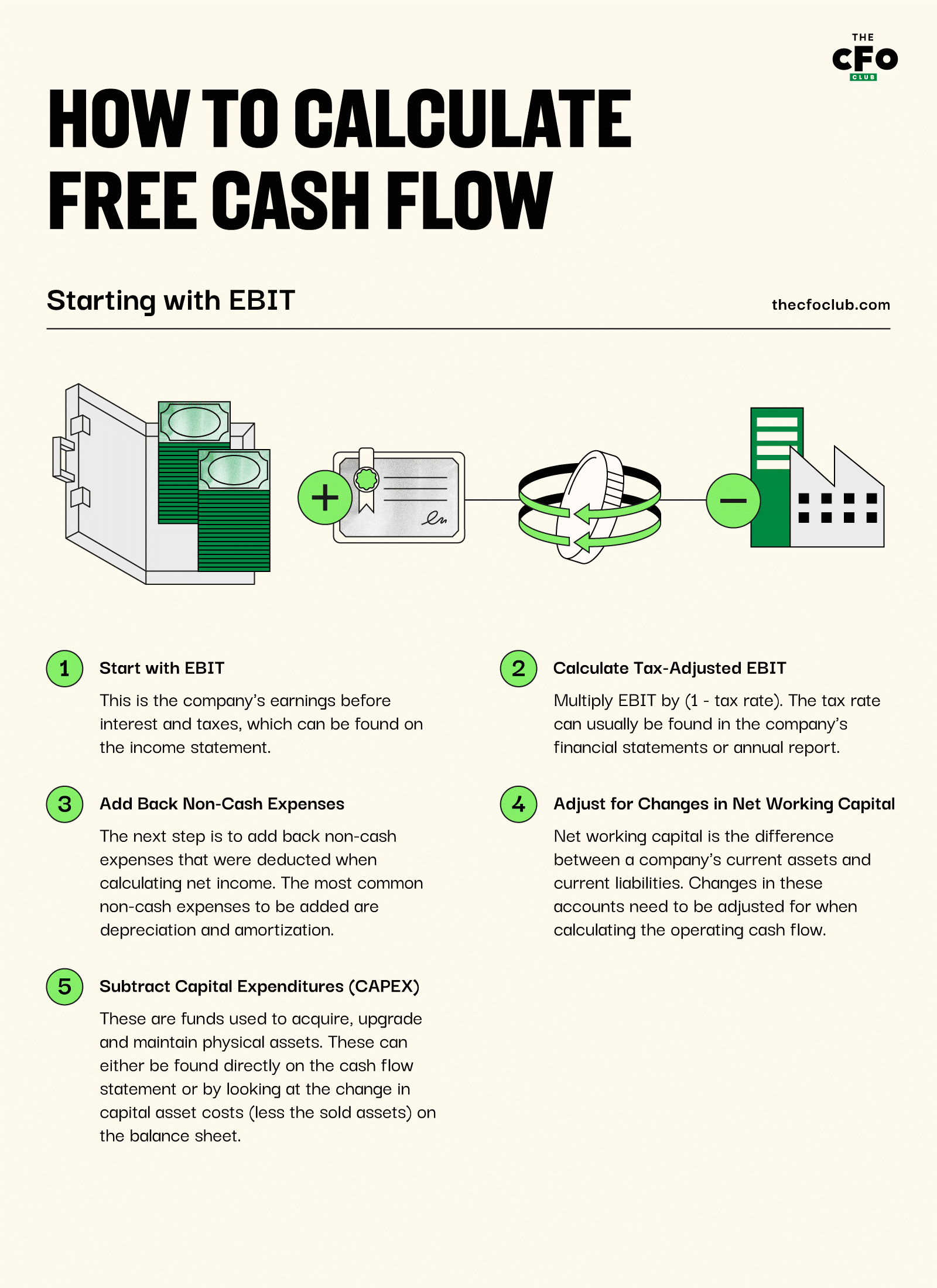

Starting with EBIT

The free cash flow equation starting with EBIT is nearly identical to the formula for starting with net income. However, if EBIT is used as the starting point, then interest expense and tax shield are innately included within the formula.

- Start with EBIT: This is the company's earnings before interest and taxes, which can be found on the income statement.

- Calculate Tax-Adjusted EBIT: Since EBIT does not account for taxes, you'll need to adjust it to reflect the taxes that would have been paid on those earnings. This is typically done by multiplying EBIT by (1 - tax rate). The tax rate can usually be found in the company's financial statements or annual report.

- Follow Steps 4-6 outlined above: Steps 1 & 2 will carry out the same results as steps 1-3 when starting with net income; as such, steps 4-6 from that approach can be repurposed here.

The advantages and disadvantages to starting with EBIT are largely the same as starting with net income - it’s usually the preferred method when EBIT is already available.

Ultimately, the method used to generate your free cash flow formula is up to the user, as there are many methods to get to the same answer. The best system to use is the one that gets you to the free cash flow number you want (ie do you want interest added back or not) and uses the information most readily available within the business.

Best Option for SaaS Companies

While “best” is a subjective term, EBIT is certainly the most popular metric within the SaaS industry. This means that industry professionals are looking at financials that are capital structure agnostic (aka this figure would be identical no matter the capital structure of a company, except for the interest-related tax shield).

If you’re looking to relate to peers and raise capital more easily, basing your free cash flow formula off EBIT as the starting point will give you a capital structure agnostic FCF, while also grounding the information in a metric that is already tracked. This will help when communicating with those in management that are less financially inclined.

If you want more tips, tricks, and information about how to best report the financials in your SaaS business, subscribe to The CFO Club’s newsletter today.