Understand Deferred Taxes: Deferred tax assets reduce future tax liabilities due to timing differences between financial and tax reporting, especially common in tech startups.

Know What Triggers: Loss carryovers, stock-based compensation, and expense timing mismatches are leading causes of deferred tax assets on the balance sheet.

Watch the Signals: Shrinking DTAs indicate improving profitability, while valuation allowances reflect uncertainty about future taxable income and realization of those benefits.

Losses and stock-based compensation are part of a tech startup’s operating DNA. These result in a lesser-known balance sheet line item called deferred tax assets (DTAs). While DTAs rarely make headlines, they can have a tangible impact on your cash flow.

In this guide, I leverage my experience as a former accountant to explain the basics of DTAs, how they end up on your balance sheet, and what happens to them over time. Let's get into it.

What Are Deferred Tax Assets?

Deferred tax assets (DTAs) are future tax benefits that result from temporary differences between book and tax accounting.

Unlike property and vehicles, DTAs are intangible financial assets. They reduce tax liability in future periods and appear on the balance sheet when:

- More likely than not that the benefit will be realized (under GAAP)

- It’s probable (under IFRS)

DTAs typically appear as long-term assets unless the benefit is expected within 12 months. They can expire if not used within statutory carryforward periods, so timely utilization is critical, especially if you’re a loss-making SaaS or tech company navigating through a burn cycle, or preparing for an IPO.

Why Are Deferred Tax Assets Valuable?

DTAs help reduce future tax liability and boost after-tax cash flows when those benefits are realized.

While this may not seem like a large sum of money to many, it can be quite a figure for capital-intensive SaaS and tech companies with high upfront costs and stock-based compensation. For them, DTAs reflect years of cumulative losses that save a significant amount of taxes once they turn profitable.

This also means DTA doesn’t always reduce tax liability, even if it’s on your balance sheet. Reduction in tax bill hinges on future taxable income—no income, no benefit.

Think of it like this:

A DTA isn’t a coupon you can redeem anytime. It’s a promise that only holds if you generate the right kind of income at the right time.

This is exactly why companies sometimes need a valuation allowance to partially or fully write down DTAs when realization is uncertain.

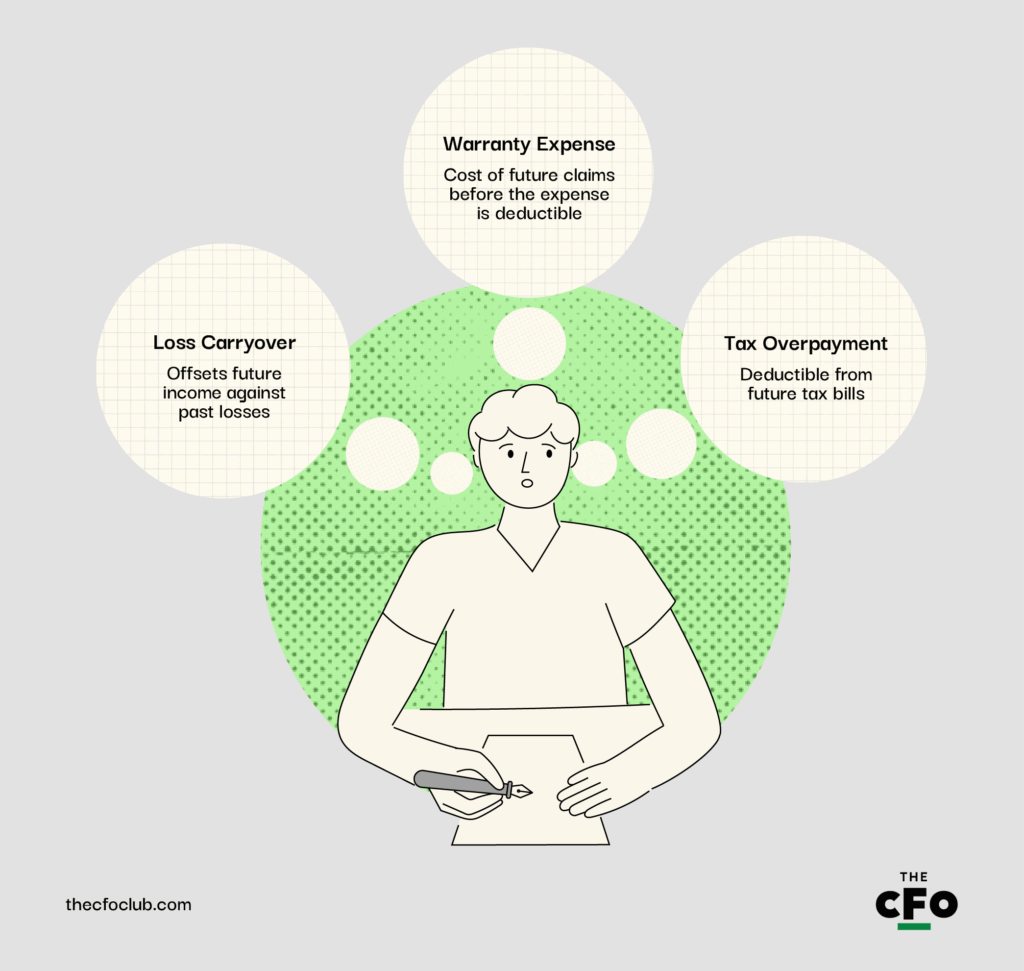

Deferred Tax Assets: Leading Events

Now that you understand what deferred tax assets are, let’s look at which financial accounting events or concepts can lead to the creation of a DTA on your balance sheet.

Loss Carryover

Loss carryover (also called a tax loss carryforward) is the option to offset future income against past losses, which creates a DTA. This is common in SaaS and tech companies that experience long burn phases before turning profitable.

For example, consider a SaaS startup that reports a $10 million net loss in 2024 due to high R&D and customer acquisition costs. Under tax law, the company can carry forward that loss to offset future taxable income, say in 2026. This reduces their tax liability and improves cash flow in 2026.

Warranty Expense

Warranty expenses create DTAs when companies recognize the cost of future claims before the actual expense is deductible for tax purposes.

Suppose a SaaS firm bundling IoT devices sells $5 million of smart sensors and estimates $500,000 in future warranty costs. This estimate hits the income statement today, but tax authorities won’t allow a deduction until claims are paid.

The result?: A DTA on the balance sheet that reflects this timing difference.

Tax Overpayment

Companies often overpay income tax due to conservative assumptions or timing differences in recognizing expenses. This surplus is deductible from future tax bills, which means it’s a DTA.

Say a tech company aggressively depreciates servers on an accelerated basis over five years for accounting purposes but uses straight-line depreciation for tax. The difference increases taxable income in earlier years, creating a DTA that will reverse in future years.

Other Common Causes for DTAs

Along with loss carryover, warranty expense, and tax overpayment, there are various other causes why DTA appears on a company’s balance sheet. Here are some other common causes I’ve experienced in my career:

- Tax Attributes: Tax attributes like net operating loss carryforwards and tax credit carryforwards (including foreign and AMT credits) result in DTAs. In fact, they’re often the most material DTAs that appear on a company’s financial statements.

- Stock-Based Compensation: Equity awards expensed in books but not tax deductible until exercised result in DTAs.

- Bad Debt Reserves: Allowances for doubtful accounts recognized early in accounting books but only deductible when debt is actually written off for tax result in DTAs.

- Accrued Expenses: Items like bonuses, commissions, and vacation pay accrued but only deductible once paid under tax law result in DTAs.

- R&D Capitalization Differences: Under U.S. tax reform (IRC §174), certain R&D costs must now be capitalized and amortized, creating a book-to-tax timing difference and resulting in DTAs.

- Revenue Recognition Timing: Under ASC 606, SaaS companies often defer revenue recognition, but tax rules may require earlier recognition, resulting in DTAs.

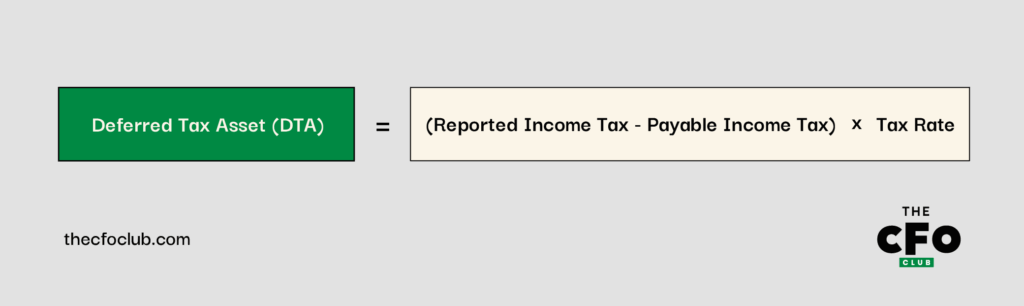

The Deferred Tax Assets Calculator

Deferred tax asset is calculated by multiplying the temporary difference between reported income tax and tax liability according to tax law by the applicable tax rate:

You can also use our deferred tax asset calculator—just input your reported income tax, payable income tax, and tax rate.

DTA Calculation Example

Suppose your SaaS company accrued $100,000 in employee bonuses in December 2024. This amount was recorded as an expense as per GAAP, but according to tax rules, the bonuses are only tax-deductible once they’re paid in January 2025.

This will result in a temporary difference that increases your current tax liability, creating a DTA. Here’s a comparison of your income statement reported as per GAAP vs. IRC rules:

| Item | GAAP ($) | IRC ($) |

| Revenue | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 |

| Operating Expenses | (700,000) | (700,000) |

| Accrued Expense | (100,000) | (0) |

| Pre-Tax Income | 200,000 | 300,000 |

| Income Tax @ 25% | (50,000) | (75,000) |

According to these statements, there’s a temporary difference in reported vs. actual pre-tax income of $100,000 because of bonuses:

$100,000=$300,000-$200,000

So, the deferred tax asset in this example would be $25,000 using the calculation above:

$25,000=$100,000 x 25%

You can also calculate this by subtracting reported tax vs. actual tax liability, which would come out to the same result of $25,000—or use our calculator.

Decreasing DTAs and What They Mean

DTAs decrease over time as the underlying temporary differences reverse. Net operating loss (NOL) carryforward is the most common driver of DTA reversal.

As per IRS rules, NOLs let companies apply losses from previous periods to offset future taxable income. When your company finally turns profitable after years of losses (typical for SaaS and tech companies), NOLs kick in and reduce taxable income. The reduction in tax liability draws down the DTA on your balance sheet.

Economically, this is a good thing. A decreasing DTA signals improving profitability. It also means your company is using its “banked” tax benefits and past losses to reduce cash outflow today.

Deferred Tax Asset Valuation Allowances

A valuation allowance is a reserve against DTA. It’s created when the company believes it’s unlikely to realize the benefit fully.

Valuation allowance is essentially accounting-speak for: “we have a tax asset on paper, but we’re not confident we’ll earn enough taxable income to use it.”

GAAP requires you to create a valuation allowance when it’s more likely than not (i.e., more than 50% likely) that part or all of the DTA won’t be used. This is often the case with SaaS and tech companies with prolonged operating losses or unpredictable revenue models.

Suppose a company has $30 million in NOL carryforwards, which translates to $7.5 million in DTA. But forecasts suggest continued losses for the next few years and no clear path to profitability. In that case, the auditor may require a full or partial valuation allowance. This reduces the DTA on your balance sheet and hits the income statement as a tax expense.

DTA allowance does not impact cash but can impact an investor’s perception of your business and trigger deferred tax disclosures.

Deferred Tax Asset vs. Deferred Tax Liabilities

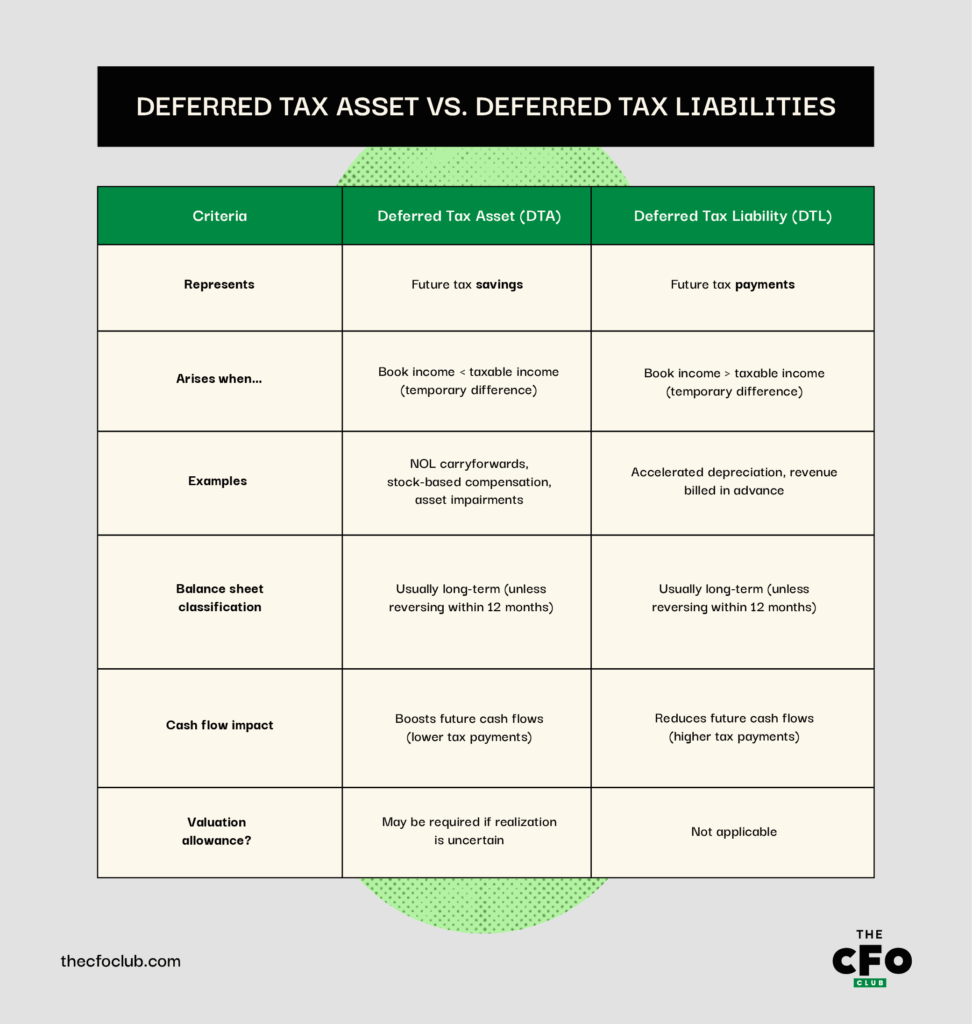

DTAs and deferred tax liabilities (DTLs) both arise from temporary differences between accounting and taxable income, but they reflect opposite outcomes.

DTL arises when a company pays less tax now but will owe more in the future because of accelerated tax deductions or deferred revenue recognition. DTLs typically stem from tax differences caused by accelerated depreciation, installment sales, or revenue being recognized earlier for tax than for book.

Here’s an overview of the differences between DTA and DTL:

If you’re ever confused about whether an event will result in a DTA or DTL, ask yourself:

- Is the company recognizing an expense today that isn’t deductible for tax until later? If yes, it likely creates a DTA.

- Has the company experienced losses that it can carry forward? If yes, it results in a DTA (NOL carryforward).

- Is the company deducting more for tax now than for books (like in the case of depreciation)? If yes, it likely creates a DTL.

- Is revenue recognized for tax now but deferred for books? It likely creates a DTL (common under subscription models).

Think of DTAs as future tax “credits” and DTLs as future tax “debts.” Managing the timing of these differences can help you influence your effective tax rate and cash flow profile.

Go Beyond Numbers

During my time in equity research, I always asked clients to think about the story the numbers were trying to tell instead of just focusing on price. I’d urge you to use the same principle here.

DTAs tell a story about the company’s past performance and future expectations. A rising DTA might reflect piling losses or temporary gaps in expense timing. On the other hand, a shrinking DTA often signals improved income or reversal of earlier timing differences. And valuation allowances? They signal caution.

Getting your story right is the key to understanding your economic reality. Ready to dive into that DTA figure on your balance sheet? Want to compound your abilities as a finance professional? Subscribe to our free newsletter for expert advice, guides, and insights from finance leaders shaping the tech industry.