Clarify Ownership Value: Accurately calculating common equity ensures you're presenting a clear, defensible view of shareholder ownership in boardrooms and capital discussions.

Protect Strategic Precision: Avoid equity missteps, like outdated earnings or incorrect share counts, that can mislead valuations, investor messaging, or funding models.

Leverage Integrated Systems: Modern finance software reduces risk, enhances audit readiness, and keeps your equity data aligned with real-time performance.

The common equity formula measures how much of your business belongs to shareholders after subtracting liabilities.

In my role as a digital software expert, I’ve worked closely with CFOs and finance executives who tell me just how essential this metric is for accurately presenting ownership value—especially in strategic discussions around capital structure, investor relations, and board reporting.

This guide will show you how to calculate common equity with precision and use it in real-world financial leadership scenarios. So when you're aligning with stakeholders, preparing for an audit, or fielding investor questions, you can clearly demonstrate the value they own, and why it matters.

But first, let’s go over the fundamentals of common equity.

What is Common Equity?

Common equity is the portion of your company that belongs to its regular shareholders. It is whatever is left after you pay off all your debts and take care of preferred shareholders.

Common Shareholders vs Preferred Shareholders

Regular or common shareholders are investors who own common stock in your company. They have ownership stakes, voting rights on major decisions, and the potential to earn dividends—but they’re last in line to get paid if your company goes bankrupt, after creditors and preferred shareholders.

Preferred shareholders receive fixed dividends and are paid before common shareholders, but they usually don’t have voting rights.

Common equity is more than a line item; it’s a signal. Investors look to it as a reflection of your company’s underlying value and financial resilience.

Equity on its own doesn’t tell the full story, but when paired with metrics like ROE, EPS, and your debt-to-equity ratio, it paints a powerful picture. These figures together shape how investors perceive risk, return, and long-term stability, ultimately influencing valuation and confidence in your leadership.

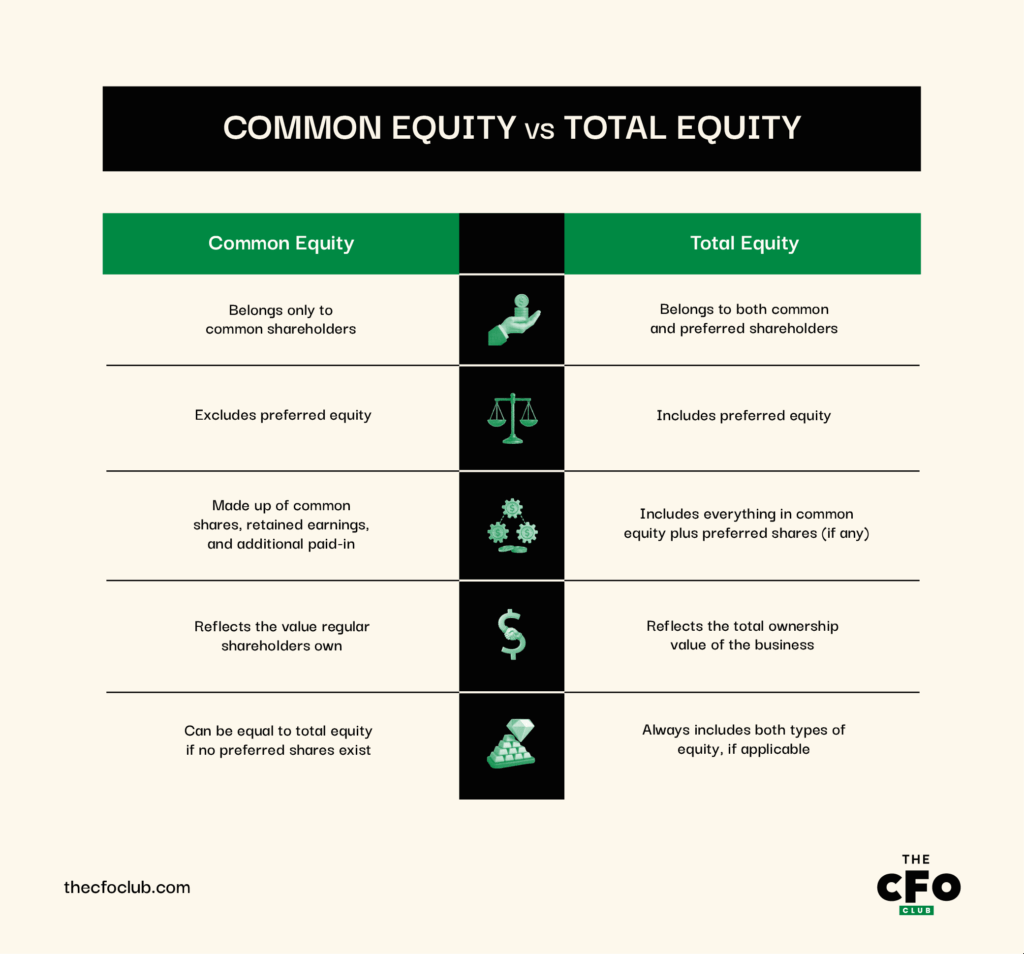

Common Equity vs. Total Equity

Common equity is the part of total equity that belongs to common shareholders. It excludes preferred equity, which belongs to those in a privileged share class with special rights.

Total equity is the entire value a company owes both its preferred and common owners.

This distinction means that common equity is a part of total equity. But if a company has no preferred shareholders, then its common and total equity will be the same. Here’s a visual representation of the key differences between the two:

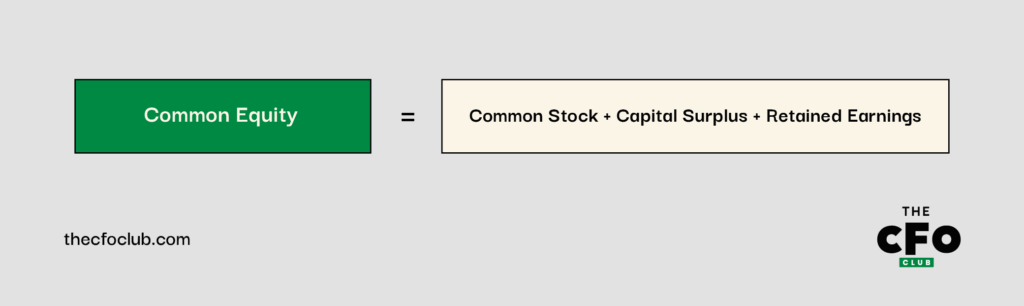

The Common Equity Formula

To get a clear picture of what your common shareholders actually own, you need to add up your common stock, additional paid-in capital, and retained earnings. Here’s how:

When we talk about common equity, we're usually dealing with three main components: common stock, capital surplus, and retained earnings.

- Common stock, or common shares, are basic shares held by regular owners. They come with voting rights and may yield dividends. For example, if a company has 1 million shares with a par value of $1, the common stock is $1 million.

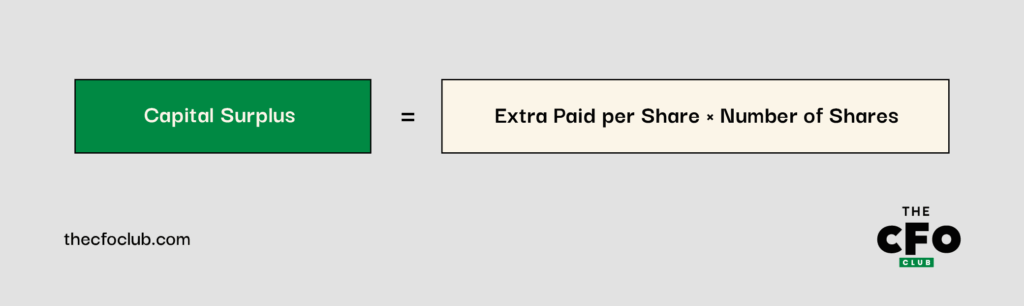

- Capital surplus is any extra money investors pay for shares beyond their face value. It is also known as additional paid-in capital. If a share’s base value is $1 but someone paid $5, that extra $4 counts here.

- Retained earnings refer to net income that a company chooses to reinvest yearly instead of paying it out to shareholders. If a firm earns $500,000 in profit and keeps $200,000 in the business, the latter is its retained earnings.

How To Use The Common Equity Formula

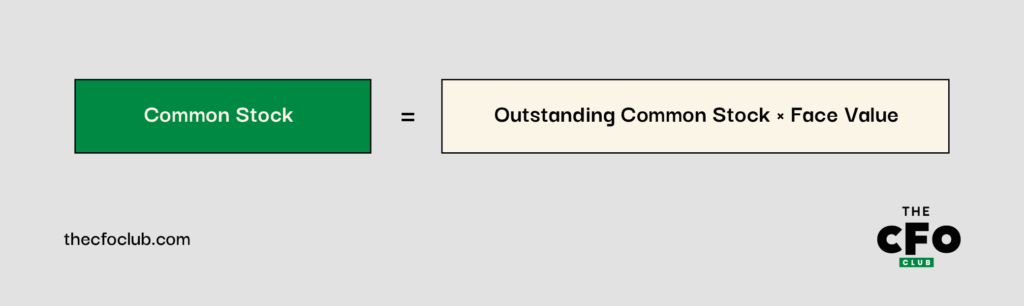

1. Find the Common Stock Amount

You’ll find the common stock amount on the balance sheet under the Shareholders’ Equity section. This is simply the total number of shares sold to investors multiplied by the cost per unit:

The formula for common stock isn’t just a math exercise—it’s a snapshot of what’s been raised from equity holders, which feeds directly into how much flexibility you have for reinvestment, capital structuring, or even share buybacks.

- Outstanding common stock is the number of regular shares that investors currently hold. They are shares that have been issued and are still active in the market.

- Face value, or par value, is the original value of each share when your company first issued it. It’s usually a small fixed amount like $1 or $0.01 per share.

Say you control finance at a software development startup called Moontech, and it has 2 million shares of outstanding common stock. If each share has a face value of $1, its common stock amount on the balance sheet would be $2 million:

2,000,000 × $1 = $2,000,000

2. Determine Capital Surplus

Next, you need to confirm the capital surplus. Like common stock, you’ll find it in the Shareholders’ Equity section of the balance sheet.

Remember Moontech? We already know the company sold 2 million shares at a face value of $1. But if investors paid $6 per share instead, it means each one brought in an extra $5 above face value.

To find Moontech’s total capital surplus, you’d multiply the extra amount paid per share by the total number of shares bought above face value:

In this case, Moontech’s capital surplus would be $10 million:

$5 × 2,000,000 = $10,000,000

3. Look at Retained Earnings

Your retained earnings are usually listed by name or grouped under a heading like “retained profits" in your Shareholders’ Equity section.

For example, if Moontech’s retained earnings show $3 million, that’s not just an accounting line—it’s a strategic signal. That $3 million represents capital the company has deliberately reinvested rather than distributed.

In other words, it’s dry powder for growth, M&A, or R&D, and a reflection of leadership’s long-term confidence.

4. Run the Calculation

Once you have all the pieces (common stock, capital surplus, and retained earnings), insert them into the common equity formula to calculate it. With the above formula, Moontech’s common equity would be $15 million:

$2,000,000 + $10,000,000 + $3,000,000 = $15,000,000

It’s a simple figure, but it anchors critical decisions: how much leverage you can take on, how investors assess your solvency, and whether you’re structurally positioned for moves like buybacks, expansion, or even an acquisition.

When To Use The Common Equity Formula

The common equity formula isn’t one you need to use every day or month, but it's important at certain periods like:

- When preparing financial reports, especially when reporting to the board or investors

- When reviewing your company’s value or net worth

- When comparing your business to others in your industry

- When doing ratio analysis, like return on equity (ROE)

- When raising money from investors who want to know how much of the company they’d own

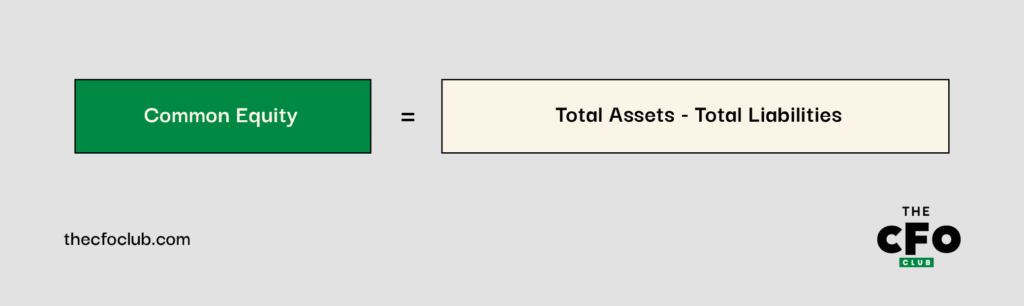

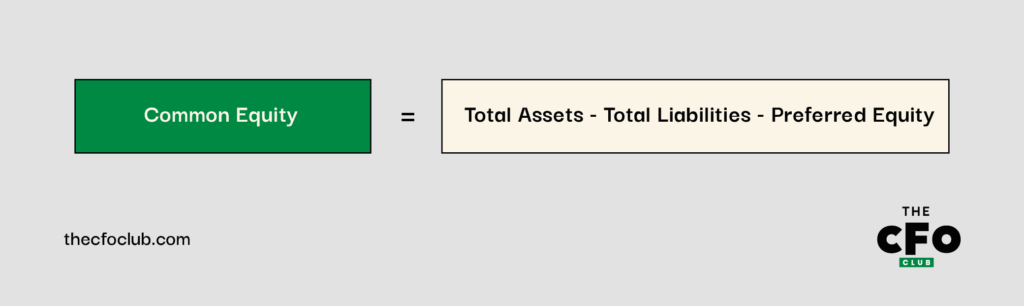

Other Common Equity Formulas

Aside from the formula above, there is a secondary, simpler calculation for common equity. Ideally, you’d use this when you don’t have access to detailed stock or earnings information, and your company has no preferred shareholders:

If your company has preferred shareholders and equity, though, use the variant below:

Think of these formulas as quick proxies for equity when you don’t have, or don’t need, a detailed breakdown. They won’t replace a full balance sheet analysis, but they’re incredibly useful when you want a top-level view of what the business is worth after liabilities.

In practice, they’re great for speeding up strategic decisions: helping you assess financial strength, cash flexibility, and return potential without slowing down your workflow.

Every financial decision is only as strong as the data it’s based on. Outdated financial data isn’t just an inconvenience—it’s a silent but deadly threat to profitability.

Mistakes To Avoid With the Common Equity Formula

Throughout my career, I’ve spoken to several CFOs. Across these conversations, a common thread always comes up when we talk about common equity: the small but costly assumptions.

These seasoned leaders aren’t misreading the formula itself; they’re misjudging what it reveals (or doesn’t) about the company’s true financial posture. Here are the recurring pitfalls they’ve pointed out, and how to sidestep them when using common equity as a strategic tool.

1. Using the Wrong Share Numbers

It’s surprisingly common to grab the total authorized shares when calculating common equity, but that number doesn’t belong in the equation. What actually matters are the outstanding shares, since they reflect real stakeholder ownership.

Using the wrong figure won’t just throw off internal reports—it can distort how the market perceives your company’s value. If your strategic decisions involve valuation, investor return modeling, or dilution risk, this input deserves a second look.

Solution:

Pull your share count directly from the latest cap table or equity management system, not from older filings or summary reports. This helps ensure you're always working with live, accurate data.

2. Missing Updated Retained Earnings

As you know, retained earnings change over time. So, if you’re referencing an old balance sheet, you might be basing your equity calculation on outdated assumptions. That can quietly distort your valuation or capital planning.

Solution:

Set a recurring reminder to check for finalized quarterlies before running any equity-based models. It’s an easy way to safeguard against using stale data.

3. Skipping the Face Value in Common Stock

Face value is typically a very low amount (like $0.01 per share), so you can easily forget to include it when calculating your common stock. But no matter how small, it’s still a critical part of the formula. Don’t leave it out.

Solution:

Lock in a template or formula in your financial model that hardcodes face value per share, even if it seems negligible. That way, it never gets lost in the shuffle, especially during high-speed scenario planning or board prep.

The Benefits of Using Software for Common Equity

Relying on spreadsheets for equity calculations can work, but it often comes at the cost of time and clarity. Accounting software streamlines the process by tying directly into your financial statements, reducing manual steps and the risk of error.

When it comes to calculating common equity, software can offer a few clear advantages:

- Fewer Errors: Since the data flows directly from your balance sheet and cash flow statements, there’s less room for manual entry mistakes or overlooked numbers. That improves the reliability of your reports—especially when speed and precision matter.

- Timely Data: Many platforms update financial data in real time, so your equity figures reflect the latest transactions. That reduces the risk of basing decisions on outdated numbers.

- Simplified Reporting: Most enterprise tools generate clean, export-ready reports. Whether you're updating stakeholders or prepping for an audit, it cuts down on time spent gathering and formatting data.

Here are some of my top picks to help you get started:

Join for More Financial Management Insights

Mastering the common equity formula is just one part of building a strong financial foundation for your business.

If you’d like more practical tips on improving reporting, making smarter financial decisions, and communicating value to your board and investors, join our community.

Subscribe to our newsletter here for exclusive insights, guides, and resources to help you stay ahead.