GAAP: Accounting's Secret Recipe: GAAP provides a structured framework for financial reporting in the U.S., ensuring consistent and transparent financial statements across industries.

The Compliance Conundrum: Public companies must follow the SEC's GAAP rules for stock exchange listings, while private firms can benefit by broadening financial opportunities and investor trust.

Dual-Reporting Dilemma: GAAP and Beyond: Some companies report both GAAP and non-GAAP measures, identifying non-GAAP separately to adhere to regulations and offer additional financial perspectives.

What is GAAP?

GAAP, or Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, are a standardized set of accounting rules, procedures, and guidelines used in the United States for preparing financial statements.

It helps financial professionals ensure consistency, transparency, and comparability in financial reporting across different organizations and industries using these principles:

- Revenue recognition

- Balance sheet classification

- Materiality

By adhering to GAAP, professionals reduce the risk of errors or misstatements, enhance credibility with stakeholders, and streamline the process of comparing financial results between companies.

GAAP Compliance

In the U.S., all publicly traded companies are required to follow the rules set out by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which includes regular filing of GAAP-compliant financial statements.

Adherence to the SEC’s rules is necessary for a company to remain publicly listed on stock exchanges, and violation of these rules can result in a company being de-listed. You can view selected Staff Accounting Bulletins on the SEC’s website, which summarizes how GAAP is to be applied by organizations.

Though private companies and nonprofit organizations aren’t strictly required to follow GAAP in their reporting, establishing this standard early keeps doors open for financing, from both equity and debt sources. For ease of analysis (and proper apples-to-apples comparisons), many lenders will require annual financial information to be prepared according to GAAP as part of their lending agreements. On the equity side, investors are commonly advised to be extremely cautious of companies whose financial statements are not prepared using GAAP.

At the end of the day, GAAP is in place to ensure that accounting methods are accurate and honest; financial institutions, investors, and individuals want to see the same.

GAAP compliance is verified through an auditor’s opinion, resulting from an external audit by a certified public accounting (CPA) firm. If you find yourself wanting to confirm GAAP compliance in your financial statements, hiring an external auditor prior to a legal requirement can expedite the process and ensure that you’re charting the right course of action.

There is another option if you find yourself wanting to report on measures that are not explicitly allowed according to GAAP rules. Some companies will report both GAAP and non-GAAP measures when reporting their financial statements, though GAAP regulations require that the latter be explicitly identified in financial statements and other public disclosures.

FASB

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) is an independent nonprofit organization that sets the standards for public, private, and nonprofit accounting in the United States. The FASB is the final authority on the establishment and interpretation of GAAP in the U.S., as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recognizes FASB as the accounting standard setter for the country.

The FASB was formed in 1973 to succeed the Accounting Principles Board (APB) and carry on its mission to ensure consistency, transparency, and integrity in U.S. corporate financial reporting. Though it was the acting authoritative body on nationwide accounting standards from 1959 until 1973, most guidelines and rules created by the APB have now been amended or superseded by FASB statements.

GAAP vs. IFRS

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are the accounting standards set by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and are considered to be the international alternative to GAAP. If GAAP rules are representative of U.S. laws, IFRS aims to be representative of the United Nations mandates: a set of rules that supersedes national borders and holds all members to the same standard.

The IASB and FASB have been working on converging GAAP and IFRS since 2002 and have made some headway, such as the U.S. removing the requirement for non-U.S. companies to reconcile their financial statements to be GAAP-compliant if they’re already IFRS-compliant. There are, however, still differences between the two sets of rules, including (but not limited to):

Inventory Costing Methods

GAAP allows companies to use Last In First Out (LIFO) as an inventory cost method, whereas this is prohibited under IFRS.

Classifying Research and Development (R&D) Costs

Under IFRS, R&D costs are considered capital investments that can be amortized over multiple periods if certain conditions are met. Under GAAP, R&D costs are considered expenses and are charged as they are incurred.

Reversing Write-Downs

GAAP specifies that an inventory or asset which has been written down cannot be reversed if the market value of the asset subsequently increases. IFRS allows this reversal.

Valuing Fixed Assets

GAAP records and reports fixed assets at historical cost, whereas IFRS enables businesses to adjust fixed assets according to fair market value.

Robots Know GAAP

Before I get into the details of GAAP, I wanted to give you an out — if you’re just trying to make sure your company doesn’t get fined, becoming a CPA isn’t the move. Look at financial reporting software instead, which can monitor this kind of thing for you:

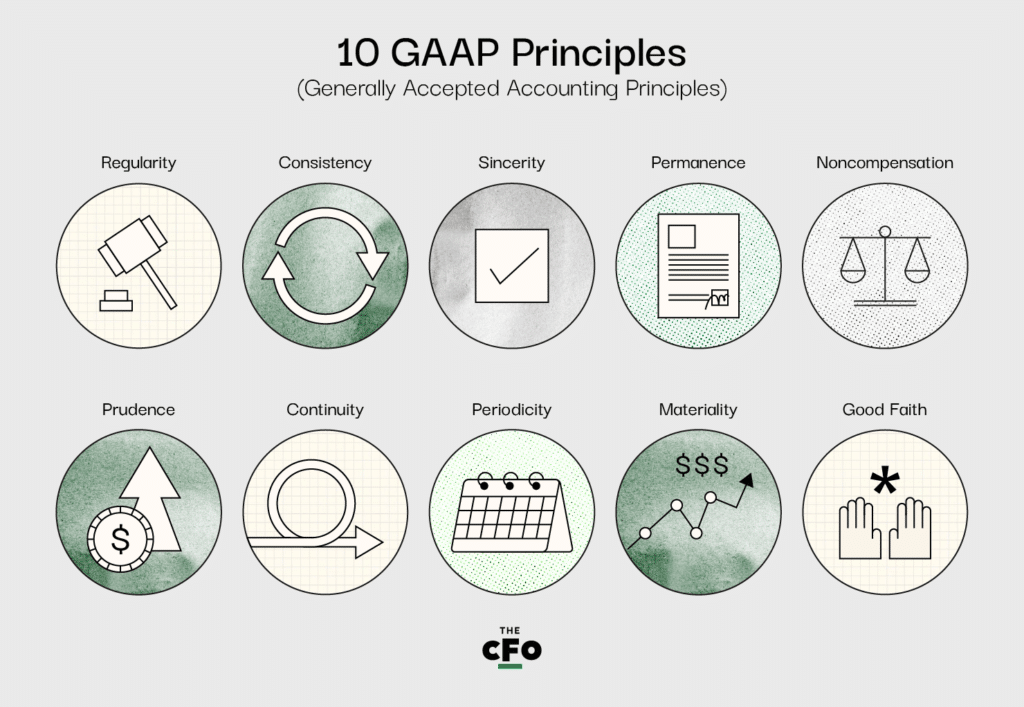

10 Key Principles of GAAP Explained

Though GAAP is made up of three different parts, the 10 key principles within the standard are its core. If you have questions about your compliance with GAAP, you should verify your practices against these principles first.

The 10 principles of GAAP are as follows:

1. Principle of Regularity

The organization must abide by all established rules and regulations of GAAP.

What does this mean?

This principle means that a business cannot pick and choose which rules it’s going to follow but, instead, needs to follow all of the rules set out under GAAP.

2. Principle of Consistency

The same standards are applied through each step of the reporting process, with any differences that may be encountered disclosed.

What does this mean?

When preparing your financial statements, you need to ensure comparability. In other words, you cannot choose to prepare your balance sheet according to GAAP but prepare your income statement differently. If you have to make adjustments between statements, you are expected to fully disclose and explain the reason(s) why in footnotes to the financial statements.

3. Principle of Sincerity

The organization strives to provide an accurate and impartial account of a company’s financial situation.

What does this mean?

Financial statements must be prepared with objectivity; if you’re trying to hide, or bring greater attention to, certain financial information, you are violating this principle. You should be preparing the financial statements as if you have no vested interest in the success or failure of the business.

4. Principle of Permanence of Methods

The same standards must be applied from one reporting cycle to the next, with any differences that may be encountered disclosed.

What does this mean?

Just like the principle of continuity, this comes down to comparability. You have to make it easy to assess statements across the board, and this principle focuses on assessment from cycle to cycle. You cannot drop the GAAP standard every second reporting cycle and maintain compliance. Once again, if you have to make changes from period to period, you are expected to comprehensively disclose and explain why in footnotes to the financial statements.

5. Principle of Non-Compensation

Both negatives and positives are reported with full transparency and without the expectation of debt compensation.

What does this mean?

You need to report everything, regardless of how it reflects on the company. You cannot try to compensate a debt with an asset or expenses with revenue on your financial statements; you must give the full, accurate picture of your company’s financial situation, irrespective of optics.

6. Principle of Prudence

Reported data must be fact-based and dependent on clear, concrete numbers.

What does this mean?

It’s natural to spend time dreaming about the future of the organization; after all, a major part of finance’s function is to create projections and share a reasonable picture of what’s to come. This principle aims to keep financial statements grounded in reality, only sharing what’s factually accurate and verifiable with data, rather than what’s speculative and subjective.

7. Principle of Continuity

When compiling reports, accountants must assume that an organization will continue to operate, regardless of the current status of the company.

What does this mean?

When valuing assets or examining liabilities, you must do so according to the textbook of finance, rather than the reality of a situation. For example, if your business realistically only has a few months of life left in it, you must still amortize your assets over years, if GAAP calls for it.

8. Principle of Periodicity

Financial entries (ie revenue recognition) should be reported within the appropriate accounting period.

What does this mean?

Accrual basis accounting dictates that transactions must be recorded in the period they occur, rather than when funds are received or disbursed. For example, if you sign a contract today that states that you will provide a service for X dollars, you must record X dollars as revenue today, not when the cash is received.

Additionally, this principle requires that accountants accurately record transactions, and do not shift time periods or alter data to change perceptions of financial statements. For example, if you had a record-breaking Q1 and an entirely lack-luster Q2 in regards to revenue, you are not allowed to shift some of your Q1 revenue into Q2 in order to look more consistent; you need to record it when it actually happened, and report it in that same timeframe.

9. Principle of Materiality

Accountants must strive to fully disclose all financial data and accounting information in financial reports.

What does this mean?

The individual (or group) preparing financial statements for an organization has an obligation to acquire all of the relevant, important information that could go into a financial statement. Anything that falls into this category is considered “material” information and needs to be reported on. This principle reinforces this responsibility and ensures that nothing is missed in the final product.

Some would say that this principle puts the accountant in accountability.

10. Principle of Utmost Good Faith

It is presupposed that all parties remain honest in all financial transactions and recordkeeping on behalf of an organization.

What does this mean?

Anyone involved in, or responsible for, the financial operations of an organization needs to be committed to honesty and integrity above all else. This principle serves to maintain an ethical standard and responsibility and is a great reinforcing argument for any financial operator that is under pressure to fudge some numbers from a superior.

Additional Guidelines

Outside of the 10 key principles, GAAP describes four constraints that are important to recognize and follow when preparing financial statements.

1. Recognition

Any and all financial statements must accurately reflect a full account of the organization’s assets, liabilities, revenue, expenses, and other financial commitments. Reports must be thorough, transparent, and not contain any modifications or omissions.

2. Measurement

Financial reporting must be prepared in a GAAP-compliant fashion, following all standards at all times. This principle reinforces the necessity for those preparing financial statements to be familiar with the aforementioned ten principles and generally accepted industry standards.

3. Presentation

All financial reports must include:

- An income statement,

- A cash flow statement,

- A balance sheet, and

- A statement of ownership or shareholders’ equity.

If any of these statements are missing, external audits or investigations may be launched.

4. Disclosure

If there is any other information needed to understand the financial reports, it must be fully disclosed in the report. A commonly used practice is to share drafted financial reports with directors, important shareholders, and other key stakeholders to record their questions. If they believe any other information is deemed necessary for understanding the reports, it should be added before the report is filed.

Implementing GAAP

Ensure that anyone establishing standard accounting methods for your organization already has a familiarity with the Generally Accepted Financial Principles and constraints, or direct them to resources such as this to build their understanding.

When it comes time to implement GAAP and prepare statements, it will be crucial to know the contents of this article like the back of your hand, so bookmark it for reference whenever you find yourself scratching your head. If you find any areas unclear, let me know in a comment below and I’ll make sure to address them right away.

If you’re wanting to improve as a financial professional and become a (better) CFO, I’ve got you covered. Subscribe to the CFO Club newsletter and keep your edge sharp through any market conditions.